I feel that I should start this series of articles with a disclaimer.

The opinions I state in this post are in no way a direct criticism of my kids’ school, which is fantastic, or any school I’ve worked in.

I’ve arrived at these opinions through various personal experiences over many years, conversations with hundreds of people at different levels of the education system, and research.

Many of the concerns I’ll talk about are completely beyond the control of anyone working in UK schools, and are not specific to any one school. They’re issues that are deeply ingrained within the system and our wider culture.

If anyone working in education reads these posts and is unhappy with anything I mention, then I apologise. I’m merely stating my beliefs based on my limited knowledge and experiences. Teachers and school staff get enough stick as it is. I certainly don’t want to add to that.

Nor is this simply a rant by a disgruntled former teacher. Sure, I left the profession unwillingly after work-related mental health issues. But I don’t feel frustration and sadness for myself.

I feel frustration and sadness for the thousands upon thousands of children and adults who are being failed by the educational system.

The purpose of this post is to raise awareness among parents of some of the major issues that affect our children in education. Our taxes pay for it, and it’s controlled by ministers we elect, so we all have a right to know what’s going on.

My worry is that most people only hear the government’s misleading platitudes, quoted at the end of nearly every article on education – the likes of “more funding than ever before” and “more children in good or outstanding schools”.

Having been a primary teacher for the last five years, I’ve encountered thousands of kids, and more and more of them seem to be finding education impossible. Of course, the pandemic hasn’t helped, and the government’s attempts to mitigate its effects have been woefully inadequate.

It’s easy to pin a lot of these problems on the pandemic. But the pandemic didn’t cause the problems I mention – it merely accelerated them to a crisis pointing they were heading towards anyway. And there are no easy fixes, as each issue is connected to and compounded by several others, as I’ll try to illustrate.

Now that my eldest child will soon be starting school, these issues are beginning to occupy more of my thoughts.

So, over a series of posts, I’ll be highlighting some of the things I feel parents should be aware of.

- Too much testing

- Drip-fed disruption

- Funding failures

- Strain on staff

- Exodus of expertise

Here’s the first one…

Too much too young: why all the testing?

Mere weeks after entering Reception, Mia and thousands of other kids will go through the National Baseline Assessment.

Whilst there’s nothing wrong with getting to know what a child can do, it’s the nature of the test and its long-lasting repercussions that concern me.

The government requires the test to be taken within six weeks of children starting Reception, which is very much a time for settling in. This time is crucial for kids and staff to get to know each other. Many kids, especially those who have never been in a childcare setting before, will find the time very stressful and the last thing they need is to be tested.

Schools will use these baseline tests to predict where the child should be seven years later. How ludicrous and unfair that the results of a test on a potentially unsettled four-year-old will shape the direction of their education for the next seven years.

Granted, many schools (Mia’s included) strive to ensure the kids remain oblivious to the fact they’re being tested, but it sets the tone for years of repressive tests when kids should be at their most explorative.

Phony phonics

In Year 1, they will need to do their phonics screening check.

Frankly, I find this whole thing bizarre. It involves kids having to decode a mixture of real words and ‘alien’ words such as chab, poil or queep. They even have little pictures of aliens next to them.

Many schools teach reading exclusively through phonics in the early years, driven mostly by the need to pass the Screening Check and the government’s relentless drive on forcing schools to teach this way.

This approach to reading reduces it to nothing more than decoding meaningless single words. It ignores the fact that written words are a form of communication that have meaning.

Doing well on the test can create the illusion that children are becoming better readers, but this isn’t the case – it simply shows they are able to recognise the sounds that certain combinations of letters represent. Reading is so much more than that.

For kids who have had a more holistic approach to reading, with more focus on comprehension and enjoyment, the test is at best, pointless, and at worst, harmful to their development.

Stifled by SATs

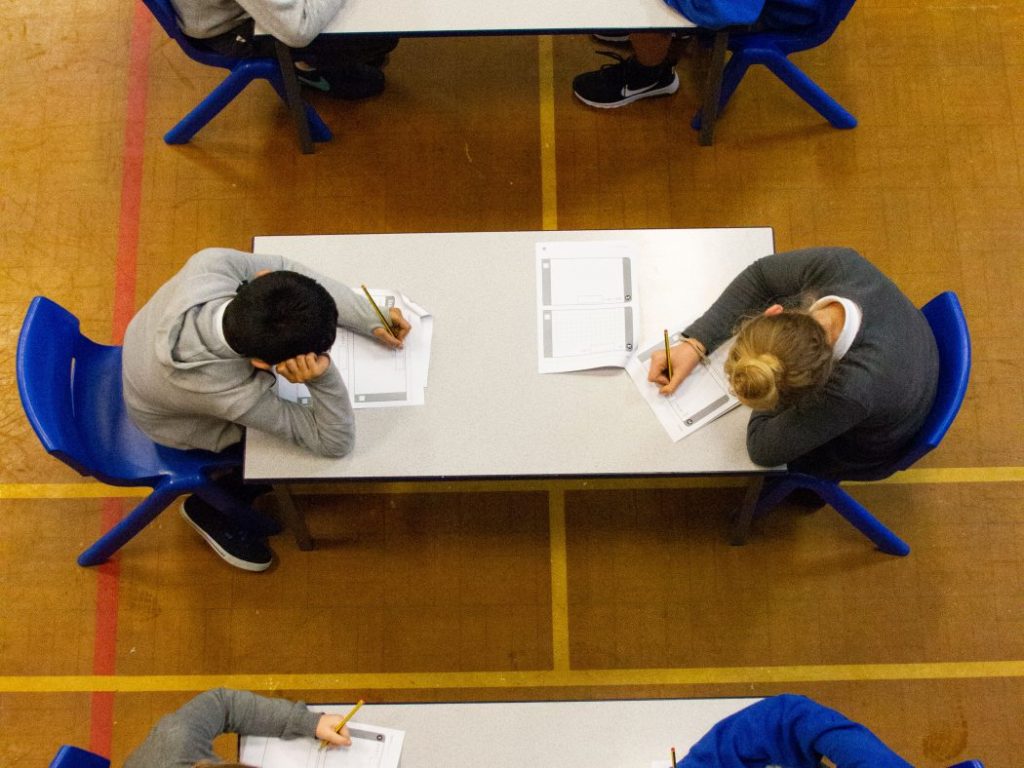

SATs (Standard Assessment Tests) cast a dark shadow over primary education.

Whilst the Key Stage 1 SATs (at age 7) will become non-statutory in 2023, the Key Stage 2 SATs (at age 11) seem like they’re here to stay.

They warp education in a number of ways (and that’s not just my opinion – even the people who advised the government on SATs have said it).

Because SATs are such a punitive accountability measure for schools, there’s a lot riding on the results. Lower than expected numbers of pupils achieve the required level, and the school can face nasty consequences, such as forced academisation, removal of staff and other upheavals, and pressure from the local community and media.

This forces many schools to adopt bad practices in their efforts to avoid these consequences – practices that do not benefit our children.

Children at risk of falling behind their expected rate of progress are often taken out of other subjects to do catch-up work on their reading, grammar or maths. The subjects most often sacrificed are the ones seen as less important – PE, music, art and languages.

The issue is, these are the subjects most likely to benefit children’s well-being, provide enjoyment and appeal to less academic pupils.

What a terrible shame that children who are at the ideal stage of their lives to explore a wide range of interests are denied the opportunity for the sake of tests that do nothing to help them.

Also widespread is a practice known as ‘teaching to the test’. Rather than ensuring children develop enjoyment and a real, deep understanding of a subject, schools often merely ‘coach’ children to answer questions as they might appear in an exam.

Whilst this can lead to a boost in test scores, it disadvantages children in the long run. My friend was Head of Year 7 at a large high school, and he told me that a huge chunk of year 7 is wasted in reassessing children whose artificially inflated SATs results are simply not a reflection of their true ability.

Many children are also woefully unprepared for the demands of high school after being spoon-fed a diet of shallow exam practice for so long.

Perhaps the worst thing about the SATs is the enormous amount of pressure it puts on children. It gets rammed down their throats so often that it’s made to feel like a life-or-death situation. And sadly, many children disengage as a result.

Naturally, many simply become bored with the repetitive drilling of exam practice. Anxiety can have a big impact, which can result in behavioural issues. And many children who are not suited to the narrow academic focus of the SATs become demotivated, struggling so much that they feel education is just not for them.

Conclusion

So there’s my first big worry about my kids’ education. That their journey in education could be reduced to a series of tests that’ll place unnecessary pressure on them, with potentially harmful effects.

The school Mia and Jude will attend does make a genuine effort to provide a holistic and enjoyable experience for their pupils. I’m confident that they will both have a good time there. And the vast majority of teachers and school leaders do not want education to be so heavily focussed on testing, but their hands are tied.

No school is immune to the pressures that bear down from the people and organisations who create, implement and monitor educational policy – who unfortunately seem very detached from the realities of schools.

Want to know more about the negative impact of testing in primary schools? Check out More Than A Score.

Why not give the 2019 grammar test a try? Do you think it’s the sort of thing that will get more 11-year-olds enjoying reading and writing?

I’d love to hear your thoughts on primary school testing.

Recent Comments