Behaviour in primary schools is getting worse.

Why is that? And how do we solve it?

It’s complicated.

There are factors beyond schools’ control. Elements of kids’ lifestyles don’t help – poor diet, no sleep, too much screen time etc. Some kids have horrendous, chaotic home lives, which make it very nigh on impossible to come to school ready to learn.

What about the things schools can control?

I’ve seen all kinds of elaborate systems that try to encourage kids to behave well. It’s always the same – some kids respond well to it, others couldn’t care less about merits, house points, dojo points, star of the week, certificates, badges, and so on.

I think the biggest reason (yet the least talked about) is that kids are expected to do so much from such a young age and are put through a relentless regime of testing?

Every school I’ve been in, it’s the same. Staff say that behaviour is getting worse. But nobody really knows what to do about it. There are countless approaches out there, from super-strict zero-tolerance regimes to more progressive, nurturing approaches. As yet, none of them has provided a lasting solution.

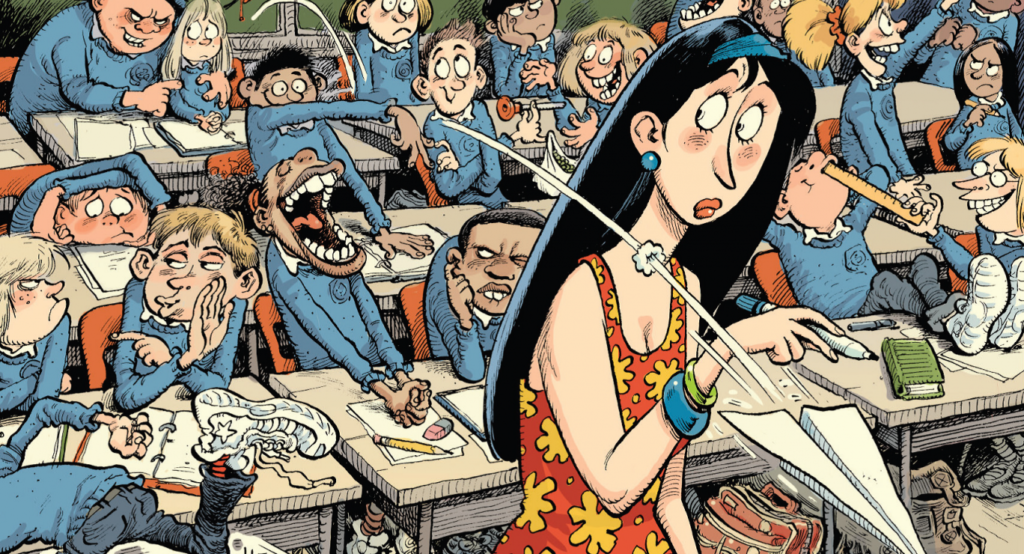

Low-level disruption = low-level learning

So much time is wasted through low-level disruption. In every school I’ve worked in, the majority of kids, who want to learn and get on with things, have their learning impacted by a few children’s constant disruptive behaviours.

These are minor things in isolation, but often they’re an endless stream of interruptions and distractions that make teaching impossible – non-stop talking, shouting out, messing with equipment, refusal to do work or follow instructions etc.

Here’s what Ofsted said about low-level disruption in their report in 2014.

“The findings set out in this report are deeply worrying. This is not because pupils’ safety is at risk where low-level disruption is prevalent, but because this type of behaviour has a detrimental impact on the life chances of too many pupils. It can also drive away hard-working teachers from the profession.”

Not much has changed since then. In fact, it’s much worse thanks to the pandemic lockdowns.

Often, teachers are very limited in what they can do about low-level disruption. Most schools have a behaviour policy that involves several reminders or warnings before any serious action is taken. In a class where there are a handful of children messing about, that can result in dozens of interruptions before anything’s actually done about it.

Even the most attentive and eager kids can struggle to focus during all that disruption. So not only is time wasted, even the children who want to learn are more likely to disengage.

The kids aren’t alright

It’s incredibly frustrating for school staff and pupils when so much learning is disrupted. But I don’t think it’s as simple as blaming the kids.

Most behaviour experts agree on one thing: behaviour is a form of communication. Children misbehave because their needs are not being met.

I’m convinced that a lot of the misbehaviour seen in primary schools arises because what they are expected to do simply isn’t reasonable.

Children are pushed into formal learning – sitting down, being quiet, reading and writing etc – from four years old. Some kids have no problems with this – usually those who are fortunate enough to have parents who’ve invested time and energy in their development. But many are just not socially, emotionally or cognitively ready.

Add into the mix a testing regime that pits kids against each other and labels some as ‘below standard’ or ‘low ability’ and you’re asking for trouble.

Recent updates to the curriculum have made it more knowledge-based. Emphasis is on the memorisation of a huge volume of information. Because of this, the school day is absolutely jam-packed.

Children in some schools barely walk through the door before they’re hustled into work. And with afternoon breaktimes non-existent once they hit Key Stage 2, and lunchtimes getting ever shorter, there’s less time for them to relax, burn energy, socialise – to just be kids.

There’s also been a trend towards moving the curriculum downwards. By that I mean, getting kids to learn things earlier in their school life.

So they have to do loads more stuff, and most of it is harder. And a fair bit of it is downright boring. I mean, why on earth does a seven-year-old need to explain the relative merits of democracies vs monarchies?

Considering all of this, is it any wonder that so many kids don’t want any part in it?

You can give a kid as many gold stars as you want, but if they’re insecure, burnt out, bored, and being made to feel like a failure, you’re gonna have problems.

What the government doesn’t grasp

I’ll finish with an interesting quote from Tom Bennett, the Department for Education’s behaviour ‘tsar’ (why are government advisers tsars these days?). It’s from a Guardian article.

“The job at that point is to help these children develop really healthy habits about how to interact with others, patience, politeness, self-regulation and compassion for others and so on. It is not enough just to say we care about the children; we have to help them.”

Whilst I completely agree with what he says – those things are central to being ‘school-ready’ – he misses what I think is a key point. These things should be in place before children start formal education. That’s not possible when kids are starting formal education at four years old. Other countries (with better outcomes for attainment AND pupil wellbeing) have a much longer pre-school period, enabling more children to be ‘school-ready’.

He also fails to recognise that teachers have to spend every available minute racing through a jam-packed curriculum (made even heftier by the missed learning of lockdowns). This means there simply isn’t time to develop these personal qualities.

Until those at the very top understand this and do something about it, there will always be problems with some children’s behaviour no matter how good the teachers are.

And that affects everyone.

Great post. I work in school and work in reception and my job is literally to manage those low level behaviours so that the teacher can get in and teach. It has got that bad that it takes a whole person a full time job to manage that, alongside obviously the bigger escalations and the underlying SEN and yet, I’m on minimum wage. Even with all of the training and qualifications. It’s literally one of the most under-appreciated jobs. Good job I really love it and am super passionate about it!

How sad that it’s got to that point.

It will only get worse as more good people leave education.

Glad you’re still enjoying it though!