Ah, The Lion King. Some say it’s the greatest Disney film of all time. It’s got it all – awesome songs, a hilarious comedy duo, a ruthless villain, tender romance. And of course utterly heart-wrenching tragedy. You know the scene – young Simba helplessly nuzzling and tugging at Mufasa’s lifeless body.

Mia and I were watching it at somebody’s house, and of course, we both shed a tear or two at that scene. But I didn’t expect what happened next. Our host, seeing Mia crying, sprang up and fast-forwarded to the end of the scene. I was quite shocked, but I didn’t say anything. I could see why they did it – to stop Mia from being upset.

It’s a normal thing to do. Whenever we think our kids might be in danger or distress, our instincts kick in and sometimes take over. But it got me thinking about our reactions when our kids encounter any kind of distress, danger or challenge.

We all want the best for our kids. Parental involvement is a huge factor in child outcomes. Kids who are loved, well-supported and cared for stand a great chance of doing well later in life.

But is it possible to be too involved in our children’s lives, too protective? When does healthy supervision and guidance become unhealthy micromanagement and restriction?

What message would it send to Mia if we fast-forwarded through every sad scene in a film? She would never experience those emotions. She wouldn’t learn how to recognise them, how to express them, how to deal with them.

There are countless other ways that we can inhibit kids’ development by intervening too early or too strongly. I’ve been guilty of a few myself.

They need to know what struggling is

I remember a time when Mia was trying to get a toy out of a box and it was stuck. She quickly got frustrated and started shouting. I immediately went over and helped her. But afterwards, I realised I shouldn’t have.

By rushing in to help her straight away, I denied her the opportunity to figure out the problem for herself. She wasn’t able to fully experience the frustration, and therefore learn how to recognise and manage it. My intervention gave her the message that if she has a problem, all she needs to do is get angry and shout, and someone will come and sort it for her.

The next time something similar happened, I quashed my paternal urge to rush in and help her. I calmly told her that shouting won’t do anything, and why doesn’t she try it another way.

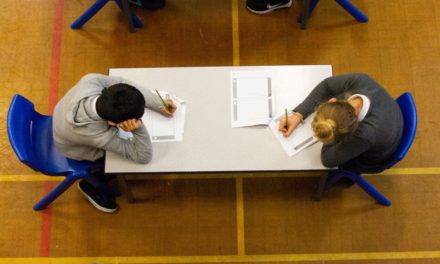

In America, and increasingly, the UK, this habit of rushing in as soon as the child seems the least bit unhappy is known as ‘helicopter parenting’. Namely, hovering over your child, ready to snuff out the slightest indication of harm or distress.

It can manifest itself in many ways. In the early years, it often involves ‘wrapping them in cotton wool’ – not allowing them to run or climb, making a huge fuss if they fall, sterilising everything they touch etc. Later on, it might be things like exerting too much control over their schoolwork or friendships.

The reasons for this are often well-meaning. We want to keep our kids safe and happy. We want them to succeed. We want them to get ahead in life.

But when parents get too involved, constantly preventing any kind of unpleasant situation, it can leave kids at a disadvantage in the long run. They may lack independence and confidence, and have low resilience and problematic anxiety.

The advantages of adversity

Children need to experience challenging situations. They are crucial for their development. Challenging situations provide opportunities for kids to solve problems, test their limits, manage risk, make decisions and regulate a range of emotions.

These instances build independence, confidence and resilience. They reinforce the idea that a child is in control of their own lives, and the crucial understanding that, yes, sometimes things don’t go smoothly, but when that happens, they’ll be able to deal with it.

The difficulty is, there’s no obvious line between what’s a healthy level of challenge or risk, and what’s potentially dangerous or distressing. That’s why, as parents, we need to constantly keep an eye on them (from a distance of course), communicate with them and make those judgements on when and how to intervene.

Before our protective instincts surge in and take control, take a bit of time to assess the situation. Instead of diving in and taking the problem out of the kid’s hands, could this be an opportunity for them to develop?

The next time your kid falls over, take a couple of seconds before rushing over. Are they actually hurt? If not, could you encourage them to pull themselves up, brush themselves down and carry on?

When they tell you that a kid at school was mean to them, our first thought might be to email the teacher demanding resolution or retribution. Instead, could you discuss it with your child, explaining that nobody gets on all the time and guiding them towards finding their own solution?

And of course, the next time they cry at a The Lion King, don’t fast-forward or turn it off. Share the experience with them and help them to understand it.

I’d love to hear your comments, stories and advice on this issue. Drop a comment below.

Recent Comments