People are often surprised and sceptical when I tell them that I quit primary school teaching due to the stress and damage to my mental health that it was causing.

Perhaps they think back to their own days in primary school, which, if they were anything like mine, were enjoyable, relatively carefree and overseen by generally happy teachers.

Unfortunately, things are very different these days, and it’s often a challenge trying to articulate that to people who aren’t familiar with modern education in the UK.

But that is what I aim to do with this post. I believe we all have a right to know what’s going on in our schools. And I believe teachers deserve more empathy and respect for what they do. (By the way, whenever I say teachers, I’m also referring to teaching assistants and other support staff, to whom these things also apply.)

First, I’m going to share a couple of statistics that show this isn’t just the personal sob story of a failed teacher, but a nationwide crisis that I’m truly worried will affect mine and thousands of other kids in their education.

Nearly half of teachers thinking of leaving

In a recent poll by the National Education Union (NEU), a staggering 44% of almost 2000 respondents said they plan to quit within 5 years.

The main reasons cited were workload, lack of trust, and decreasing pay.

Even if fewer than 44% followed through with this, the effects on a system that’s already nearing breaking point would be disastrous,

Think of all that experience and expertise that would be lost.

And what if those teachers couldn’t be replaced? It could lead to larger class sizes. Classes might need to be covered by unqualified staff, or staff that are already breaking under the strain of their massive workloads.

Either way, the education of kids will suffer.

And it’s not just the teachers who leave that are a cause for concern…

Teachers on the brink

The NEU poll also found that two-thirds of teachers felt stressed 60% of the time.

And the largest study into teacher wellbeing, the Teacher Wellbeing Index – carried out by the Education Support charity alongside YouGov – found that 78% of educational professionals experienced behavioural, psychological or physical symptoms due to their work, with 34% reporting issues with their mental health. The full breakdown of the report makes for interesting reading.

What does this mean for our kids?

It means that the staff working with them are likely to be struggling – they might be on the brink of a breakdown, burnt out, exhausted, unable to teach to their best ability, perhaps even resenting their job.

I know this because I’ve been there. At my lowest ebb, I remember remarking to my colleague and friend that I wouldn’t want my kids to be taught by a teacher like me.

And I’ve had countless similar conversations with staff in the many schools I visited as a supply teacher.

I’m also a member of a Facebook group called Life After Teaching, which provides advice and support for teachers who are struggling. It’s now approaching 80,000 members and more join every day.

Dozens of posts every day illustrate the struggles that teachers are going through all across the UK.

Let’s go a bit deeper into the issues that are causing teachers to struggle and in many cases, quit.

Wacky workload

Teachers in the UK work longer hours than those in any other developed country, with an average of 47 a week hours in term time. A quarter of British teachers work 60 hours a week.

Some people have a frustrating misconception that teachers’ work finishes when the kids leave school. In fact, most teachers spend more time on jobs outside the classroom than they do actually teaching.

In other countries with much better outcomes for children’s attainment, such as Finland, teachers work much shorter hours.

So where does all this work for British teachers come from?

Box-ticking and hoop-jumping

I believe a large part of it stems from a punitive and problematic accountability system driven by government policies and Ofsted.

There’s a palpable fear in many UK schools that the inspectors will show up and tear the place apart if the latest guidance isn’t followed to the letter.

This leads to a culture in education where everything, absolutely everything has to be evidenced, which creates mountains of administrative work for teachers.

Detailed schemes of work must be written and rewritten whenever the government publishes new requirements for the curriculum.

The volume of content that must be ploughed through is vast. And a relentless testing regime pressurises teachers to cover it all, limiting autonomy and creativity.

Some schools require teachers to provide detailed weekly plans. Teachers need to evidence how they are catering for the diverse needs of kids in their classes. This often requires them to create several variations of tasks for every lesson.

With primary school timetables now jam-packed with 5 or 6 separate lessons each day, this results in hours and hours of planning and resource creation every week.

Teachers are legally required to get 10% of their teaching time as PPA (Planning, Preparation and Assessment). This doesn’t come close to the amount of time needed to plan a week’s worth of lessons. It means teachers must spend their evenings and weekends planning.

Additionally, many primary schools require every piece of work to receive written feedback, despite there being very little solid research to show that it helps children progress. This can often result in 120 or more books needing to be marked in a day – more time working outside of school hours.

There’s a raft of other things that eat away at teachers’ time:

- Inputting and analyzing data from assessments.

- Dealing with and recording an increasing number of behaviour and mental health issues.

- Carrying out extra responsibilities. Ofsted’s latest guidance states that all subjects must be given equal priority. Most primary teachers now have some form of responsibility for a subject within their school. Most receive no additional pay and very little additional time, if any.

- Staff reductions due to funding cuts mean staff have to take more work on in general.

All of the things I’ve mentioned make it harder for teachers to do what they do best – teach our kids.

It isn’t just a case of teachers being lazy, disorganised, or undisciplined in their work habits. I’ve known the most organised, diligent and professional teachers buckle under the strain. I’ve seen others go through divorce because the demands of their job have taken over their personal life.

And though it is school leaders who implement these damaging accountability measures, they are forced to do so by the pressures placed on them by the government and Ofsted. I’m certain the vast majority would run their schools differently if they had the choice.

Many of them are in the impossible position of ensuring they fulfil their legal obligations whilst trying to look after the well-being of their staff.

Seriously stressed staff

Stress is serious in teaching.

The sort of stress that keeps people up at night, makes them dread going into work, and that makes them wish they had some sort of accident or illness that will prevent them from going in.

I’ve felt this sort of stress, and I’ve heard so many other teachers talk about their experiences with it. In the Life After Teaching group, there was a story that became a sort of symbol of what a lot of teachers were struggling with.

A teacher shared that on her drive to work, there was a particular tree, and every morning, she would have to resist the urge to drive her car into it. Every morning, she dreaded going into work so much that all she could think about was driving her car into the tree, to hospitalise herself and therefore avoid work.

Is that what we want for the people who are educating our children? Why do so many teachers feel this way?

Of course, the sheer amount of time spent working is a big factor. But there’s more to it than that.

Heart and soul

I believe teachers suffer so much stress because they give so much of themselves to the job.

Sure, there are countless demanding, difficult and draining jobs out there. I’m not saying teaching is any harder than those. But teaching is a unique job.

Every day, teachers need to perform, to stand in front of a group of people and try to motivate, guide, connect with and care for them.

There’s no switching off, no shutting your office door, no coasting through the day.

No matter how teachers are feeling, or what they’ve got going on in their personal lives, they need to block it all and put on a show for kids and parents day in, day out.

And they form a strong emotional connection with the kids in their class, whether they want to or not. In primary school especially, the teacher becomes like a parent to many children.

In addition to the hours a day they spend with their pupils, so much of their time outside the classroom is spent thinking about them. When I was a teacher, I spent most of my Sundays ignoring my own kids as I planned lessons for the kids I taught.

Like those who work in healthcare, social care, emergency services, charities and so on, teachers are conscientious people.

They will endure all sorts of hardships because they’re in it to help others, to make a difference. These hardships leave a mark, but teachers carry on because the kids they teach come first.

For these reasons, teaching is more than just a job – it is part of who you are. More so than most other jobs.

And that’s why, when teachers feel like they’re not able to do the job to the best of their ability, it takes such a toll on them.

When your superiors fail to recognise your sacrifices and criticise every minor detail. When the things you’ve done successfully for over twenty years are no longer good enough because there are shiny new (often dubious) ways of doing things. When you simply can’t keep all the plates spinning.

It hurts. It feels like you’re not good enough as a person.

I think this is what’s driving more and more teachers away. It’s why I believe teacher well-being in the UK is reaching crisis point.

And to make things worse, even the financial incentives to remain in education are being eroded.

Paltry Pay

Of course, the aftermath of Covid and the current crisis with Russia have affected the economy and everyone is suffering. But the pressure on teachers to do more for less has been growing for over a decade.

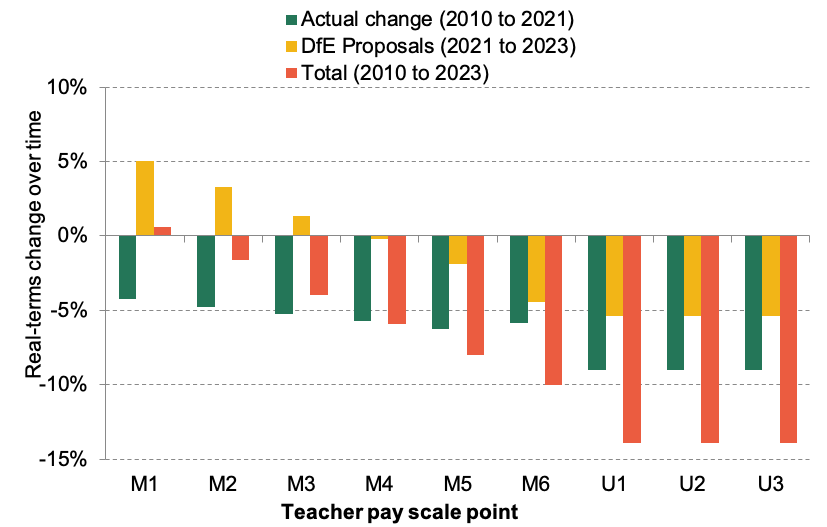

Since 2010, teachers and school staff have seen a real-terms pay cut of 14% thanks to pay freezes and below-inflation pay rises.

The government pledged to increase starting salaries to attract more people into the profession. But that’s the easy part – keeping them is the issue. Retention is a bigger problem than recruitment, and as you can see, the more experienced teachers are the ones losing out.

It’s incredibly demoralising for teachers when every year they see the unions having to fight and plead with a government that simply doesn’t value teachers.

To put it into context, I left teaching on the 4th tier of the main pay scale, £31,000 a year at the time. Sounds pretty good on paper. Many people would bite your hand off for that kind of salary.

But taking into account the hours I actually worked – approaching 60 hours a week in term time plus a couple of days in every holiday – then it worked out just over 12 quid an hour.

That’s about what you’d pay for a decent babysitter.

I could have worked that many hours in a supermarket and earned only slightly less.

Frustrated teachers regularly comment that they see their friends earning much more than them, despite doing far less training, working far fewer hours and in jobs that you could argue contribute much less to society.

Sadly, more and more teachers are deciding that they’d be better off doing something else.

And it’s our children that’ll suffer for it.

Recent Comments